Top:

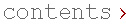

The old prioress Madame de Croissy (Sheila Nadler, holding crucifix) rages against her impending death, to the shock of Mother Marie (Dana Beth Miller).

Above:

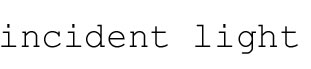

Sister Blanche (Emily Pulley) and Mother Marie (Dana Beth Miller) in Blanche's former home, where she is now a servant, after the nuns were forced to leave their convent.

Right:

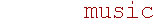

A crucial aspect of Eric Einhorn's stage direction was the transformation of the crowd from leering bloodlust (top) to horror as the nuns are felled by the guillotine (bottom).

(Production photos by Mark Matson, courtesy Austin Lyric Opera.)

Austin Lyric Opera

Poulenc's 'Dialogues of the Carmelites' speak with compelling power and subtlety

April 20, 2009To say that Austin Lyric Opera has attained a new pinnacle with its superb production of Francis Poulenc’s “Dialogues of the Carmelites,” which opened April 18 in the Long Center, is to understate the achievement. Despite the strength of its music and the horrific drama of its final scene, “Dialogues” does not score its theatrical points easily, in large part because its characters (and its composer) did not score their moral points easily.

George Bernanos’s libretto for “Dialogues” is based loosely, via a novel by Gertrud von le Fort, on a historical event: On July 17, 1794, that access of populist enthusiasm known as the Reign of Terror delivered 11 nuns, three lay sisters and two servants to the spot now called Place de la Nation in Paris, where they knelt and chanted the “Veni Creator” before ascending the guillotine.

The Holy See beatified the martyred Carmelites in 1906, but Poulenc and Bernanos took care not to beatify them before the fact. Avoiding simplistic reverence, “Dialogues” examines the collisions of duty and fear, community and self, conviction and accommodation -- collisions that unfold uniquely in every individual but are always, in real life, messy. In a way, “Dialogues” parallels the central ambiguity in Poulenc’s own life: He was both devoutly Catholic and devoutly gay.

The theatrical challenge is that the meat of the opera is its psychological specificity and complexity, which are conveyed mainly through (sung) dialogue -- thus the title -- and the supple score rather than in overt plot points. Too, the structure of fairly compact scenes alternating with orchestral interludes can hinder the dramatic arc.

In order to connect authentically with the audience, “Dialogues” demands an extraordinary depth of understanding from the entire creative team, in addition to a shipload of powerful singing. And that is what it got in Austin.

At the center was the unflinching, astutely observed naturalistic stage direction of Eric Einhorn. He consistently found appropriate action to connect scenes across the orchestral interludes, and his crowds were frightfully convincing.

Two scenes merit special notice:

At the end of Act I, we see the full measure of rage and disillusionment in the bad death of the old prioress, Madame de Croissy, and thus the full measure of dissonance between her “spiritual exhaustion” and the mask she wears in her valedictory to the opera’s central character, the novice Blanche de la Force, who has entered the convent to escape the threatening world and times. (The historical Madame de Croissy did not die badly or otherwise in metaphorical Act I but was among the martyred in Act III.)

In the final scene, Einhorn’s signal contribution was the reaction of the crowd. Laughter and bloodlust gradually give way to horror and disgust as the nuns are beheaded one by one. In many productions, the crowd is marginalized or absent from the final scene, so that the audience’s attention is entirely on the nuns. But Einhorn gets it right: It is the reaction of the crowd, its revulsion against its own handiwork, that gives meaning to the nuns’ martyrdom.

(text continues below photograph)

The scenic design, by Harry Frehner and Scott Reid for a 2002 production by Calgary Opera, hewed to the spare essentials, placed starkly against a black background.

Shawn Kaufman’s lighting design, illuminating in every sense, was no mere afterthought but was fully of a piece with the set and the music. Robert A. Dahlstrom’s costumes were designed for a somewhat less minimalistic Seattle Opera production of 1997, but they complemented the Calgary decor well enough.

ALO principal conductor Richard Buckley proved an ideal interpreter of the score -- its variegated colors, its theatrical strokes, its wide emotional range and above all its pulse. The orchestra was splendid.

Ditto the singing. Soprano Emily Pulley’s instrument may have been a shade too robust to convey Blanche’s fearful personality, but the voice was warm and flexible, and capable of wonderful color inflections. Mezzo-soprano Dana Beth Miller was a powerhouse in the role of the assistant prioress, Mother Marie. Soprano Jennifer Check delivered some glorious singing as the new prioress, Madame Lidoine. Soprano Suzanne Ramo’s bright, gleaming voice was a perfect match for the role of Sister Constance, the novice who is perpetually amused. Mezzo-soprano Sheila Nadler gave a stunningly powerful portrayal of Madame Croissy.

Among the male roles, top marks go to the limpid, youthful tenor of Scott Scully, as Blanche’s brother, the Chevalier de la Force.

Mike

Greenberg

“Dialogues of the Carmelites” continues April 22 and 24 at 7:30 pm and April 26 at 3 pm in the Long Center for the Performing Arts, Austin. See www.austinlyricopera.org. To be safe, allow two and a half hours for the drive from San Antonio.